Chosen Period: Industrial Revolution

POD: James Watt’s improved steam engine explodes during testing, killing several investors and halting financial support.

- Overview

- Short-term Consequences

- Long-term Consequences

- Everyday Life (100 years on…)

- Timeline of Events

Overview

| Government: | Weak central governments; strong regional councils |

| Economy: | Water-driven industry; limited heavy machinery |

| Technology: | Slow development; late adoption of engines |

| Social Values: | Local identity; environmental conservatism |

| International Relations: | Maritime empires dominate |

| Everyday Life: | Rural lifestyles persist longer |

| Key Conflicts: | Competition over river systems and waterways |

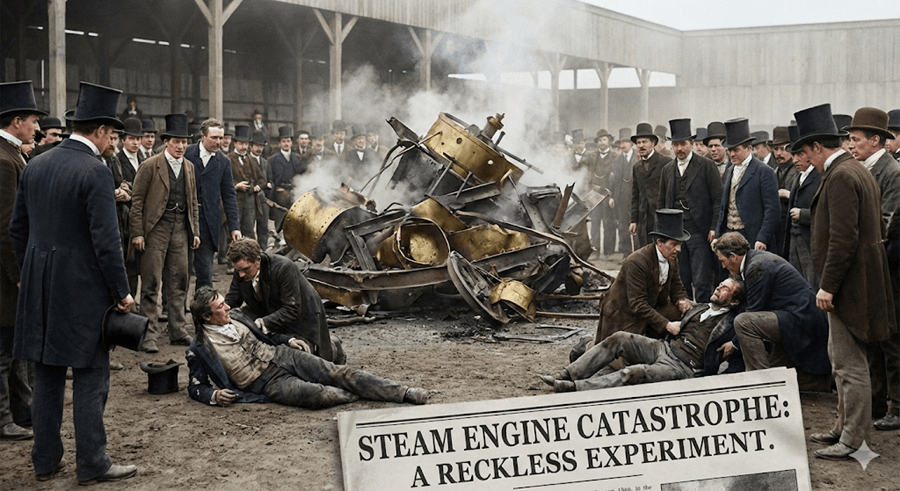

In our alternate timeline, the course of industrial progress shifts dramatically after James Watt’s improved steam engine explodes during a high-profile demonstration for key investors and government officials. The accident kills two financiers and injures several engineers, instantly branding steam technology as dangerous and unpredictable. Newspapers sensationalize the failure, calling the machine “a reckless experiment in mechanical fire,” and public opinion turns sharply against industrial innovation. As a result, early industrial development loses its central engine, literally and figuratively. Financial backing dries up overnight, and policymakers refuse to support further experiments involving high-pressure machinery. The Industrial Revolution, instead of accelerating rapidly, unfolds in an entirely different pattern: regional, slow, and heavily dependent on water-based and manual power.

| Feature | Real Timeline (Our History) | “Steam Engine Failure” Timeline |

| Primary Power Source | Steam (Coal), later Oil & Electricity. | Water (Hydraulic), Wind, Muscle, later Hydro-Electric. |

| Key Transport | Railways & Steamships (Rapid, cheap). | Canals, Rivers, Horse-drawn (Slow, expensive). |

| Urbanization | Explosive. Massive migration to industrial slums (Manchester, Chicago). | Gradual. Population remains distributed in rural towns and river valleys. |

| Social Structure | Rise of the Industrial Capitalist and the Urban Proletariat. | Dominance of Aristocracy and Craft Guilds. |

| Political Movements | Marxism, Unionism, Chartism, rapid democratic reform. | Traditionalism, Regionalism, slow/stalled democratic reform. |

| Geopolitics | Imperialism penetrates deep inland (Africa, Asia). | Imperialism limited to coastlines; inland powers struggle. |

| Environment | Heavy pollution (smog), deforestation, resource depletion. | Clean air, preserved forests, but heavy modification of rivers. |

Short-term Consequences

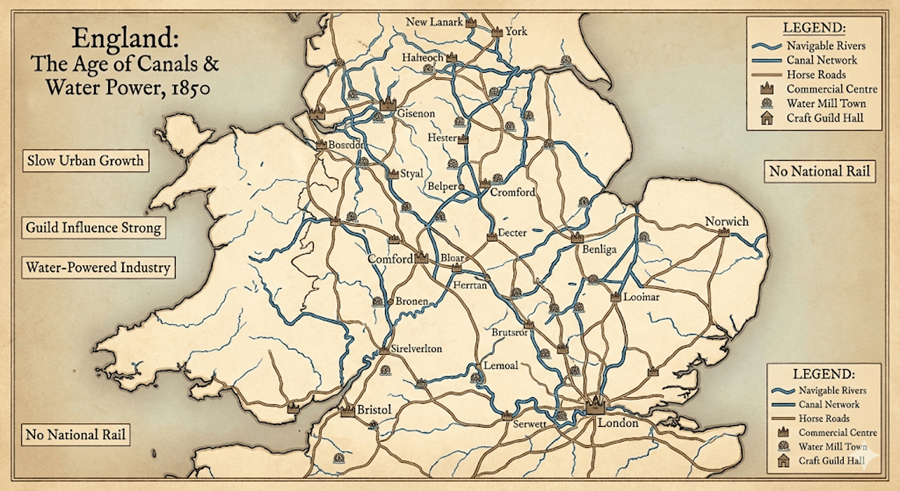

In the short term, factories remain small, scattered, and rural, located only near reliable rivers and streams. Without the steam engine to power large machines, no major industrial centers emerge in Manchester, Birmingham, or Lille. Cities across Europe grow at a much slower rate, remaining primarily commercial hubs rather than industrial powerhouses. As factories stay small, the early working class develops more gradually and remains tied to local economies. Migration from countryside to city does not occur at the same speed or scale, preventing the explosive urban overcrowding seen in our real timeline.

This slower urbanization significantly changes social dynamics. Without huge factory populations demanding reforms, political pressure for worker protections, safety regulations, and unionization emerges decades later. Governments treat labor disputes as local rather than national issues, delaying the rise of mass political movements such as socialism and organized labor. In Britain, for example, mechanized textile production grows slowly, allowing craft guilds to retain their influence well into the nineteenth century. Additionally, transport remains almost entirely dependent on canals, rivers, and horse-drawn vehicles, creating geographically isolated economies within the same country. The absence of rapid industrial growth stabilizes traditional social hierarchies longer than in our world, with aristocratic landowners maintaining political dominance due to the lack of powerful industrial capitalists.

Technologically, short-term innovation stagnates. Attempts to repair or redesign the steam engine repeatedly fail because investors refuse to fund high-risk prototypes. Educational institutions shift their focus toward mechanical water systems and chemistry rather than mechanical engineering. Small-scale inventions do appear, but none are transformative enough to shift Europe into the full momentum of industrial capitalism.

Long-term Consequences

In the long term, the most far-reaching consequence is the collapse of early railway development. Without reliable engines, railroads are not commercially viable. Horse-drawn or gravity-powered rail systems exist in limited mining regions, but national rail networks do not develop. As a result, rail lines appear only in the late nineteenth century, and even then, they remain fragmented, expensive, and unreliable. The absence of railroads radically reshapes geopolitics and economics. Coastal nations with strong navies—Britain, the Netherlands, Portugal—dominate global trade far more completely, while inland regions such as central Germany, Poland, and Austria struggle to keep pace. The lack of cheap inland transport also prevents mass industrial exports, shifting global trade toward maritime goods and raw materials rather than manufactured products.

By 1850, Europe is technologically uneven, with pockets of experimentation but no continent-wide momentum. Nations develop inwardly rather than outwardly; diplomacy focuses on controlling rivers, canals, and port cities rather than colonies or foreign markets. This leads to numerous regional disputes over waterways, especially in the Rhine, Danube, and Po valleys. International alliances form around river systems rather than ideological blocs.

This leads to numerous regional disputes over waterways, especially in the Rhine, Danube, and Po valleys. International alliances form around river systems rather than ideological blocs.

Everyday Life (100 years on…)

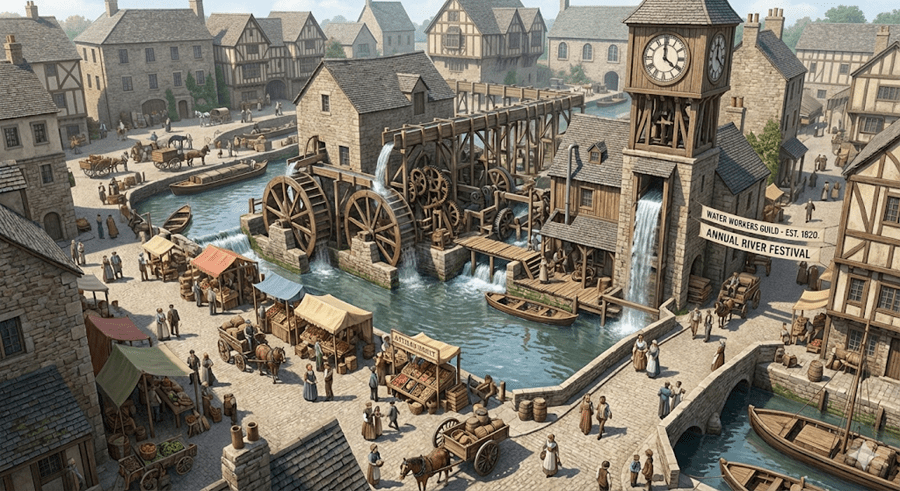

By 1900, everyday life remains far more local and traditional. Most families live within the same region for generations, and long-distance travel is rare and expensive. River towns become cultural centers, hosting trade fairs and artisan markets. Communities maintain strong regional identities based on geography and local craft traditions rather than national industrial culture. Education focuses on practical trades and water engineering, and technological innovation centers on improving mills, canals, and agricultural tools rather than engines and heavy machinery.

Although progress is slower, environmental damage is significantly reduced. Without coal-powered engines, air pollution remains low, and forests survive at higher rates. Rivers, however, become highly regulated and contested, sparking conflicts over dams, water rights, and flooding rather than over industrial markets or colonies.

This alternate world remains shaped by a single failed invention, yet its ripple effects redefine politics, society, economics, and the environment. The explosion of one prototype steam engine becomes the moment that reshapes the entire trajectory of global development, proving how profoundly one technological failure can redirect human history.

Timeline of Events

The Era of the Great Stagnation (1775–1815)

- 1775: The Birmingham Calamity During a heavily publicized demonstration at the Soho Manufactory, James Watt’s prototype steam engine suffers a catastrophic boiler failure due to a faulty valve. The resulting explosion kills financier Matthew Boulton and two visiting government officials. Watt is critically injured and branded a “merchant of death.”

- 1776: The Safety in Mechanics Act The British Parliament, under pressure from the landed gentry who fear industrial encroachment, passes the Safety in Mechanics Act. This effectively bans the development of “high-pressure thermal engines,” halting steam research in Britain. France and Prussia follow suit shortly after, viewing the technology as volatile and militarily useless.

- 1790: The Water Frame Consolidation Without steam to power mills anywhere, the textile industry becomes exclusively hydrologic. Richard Arkwright’s water frame becomes the apex of technology. Factories are forced to remain deep in the Pennines and the Scottish Highlands, tethered to fast-flowing streams. Manchester remains a mid-sized market town; the projected population boom never arrives.

- 1805: The Stalemate of Trafalgar Napoleonic Wars are fought with strictly wind-powered navies. Logistics on the continent are a nightmare without early industrial transport. The wars drag on longer but with less intensity, as moving massive armies and supplies across land remains slow and incredibly expensive.

The Age of Canals and Guilds (1815–1850)

- 1820: The Great Canal Expansion With the concept of the “steam locomotive” dismissed as a fantasy of the reckless, investment pours into water transport. The “Grand Union Canal” project in Britain is expanded to triple its original width to accommodate heavy horse-drawn barges.

- 1832: The Failure of the Reform Act In our timeline, the 1832 Reform Act gave voting rights to the rising industrial middle class in cities like Birmingham and Manchester. In this timeline, those cities are politically irrelevant. The Act is defeated by the House of Lords. The aristocracy retains absolute control over Parliament; the “Rotten Boroughs” remain.

- 1840: The “Craftsman’s Compromise” Instead of the Luddite riots (which in our timeline were reactions to rapid mechanization), a stable equilibrium is reached. Powerful Craft Guilds regulate the speed of production in rural water-mills. The working class remains semi-agrarian, often farming in the summer and weaving in the winter. The concept of the “proletariat” does not form.

- 1845: The Gravity Rail Experiments Mining concerns in Wales attempt to build rail networks. Without engines, they utilize complex pulley systems and gravity slopes. While useful for local coal extraction, the technology proves impossible to scale for national travel. The “Railway Mania” bubble never inflates.

The Hydro-Political Era (1850–1880)

- 1852: The Rhine Toll Wars Central Europe, landlocked and desperate for trade routes, falls into chaos. Prussia, unable to move goods cheaply by land to the coast, attempts to seize total control of the Rhine. The Netherlands, backed by Britain’s dominant sailing navy, creates a blockade at Rotterdam. The conflict cements the divide between “Maritime Powers” (rich, global) and “Continental Powers” (stagnant, agrarian).

- 1861: The Fragmentation of the Americas The American Civil War begins but stalls. Without railroads to move Union troops and supplies quickly across the vast distances, the North cannot effectively invade the South. The war ends in an uneasy armistice in 1865. North America remains a patchwork of regional territories rather than a unified industrial colossus.

- 1870: The Scramble for the Coasts The “Scramble for Africa” is limited to the coastlines. Without shallow-draft steamships to navigate up the Congo or Nile rivers against the current, European powers cannot penetrate the African interior. Indigenous inland empires remain sovereign, trading with Europeans only at coastal forts.

The Turn of the Century (1880–1900)

- 1885: The Rise of “White Coal” (Hydro-Electricity) Skipping the age of steam, scientists in Switzerland and Northern Italy perfect the water turbine for electricity generation earlier than in our timeline. However, transmission technology is poor. This leads to the “Alpine Miracle,” where mountain regions suddenly become the most technologically advanced areas in Europe, lighting their towns with electricity while London and Paris still rely on gas and oil lamps.

- 1892: The Danube Accords After decades of skirmishes over water rights, the Austrian Empire hosts a summit to regulate the flow, damming, and pollution of the Danube. It is the first major international body focused on environmental resource management.

- 1900: The Quiet Century The world enters the 20th century in a state of pastoral stability.

- Demographics: London has 2 million people (vs 6.5 million in real history). Pollution is negligible; the famous “London Fog” (smog) never happens.

- Society: Social mobility is low. People are born, live, and die within a 20-mile radius. News travels at the speed of a horse.

- Technology: The bicycle is the crowning achievement of personal transport. Engineering is focused on pneumatics, clockwork, and hydraulics.

- Politics: Socialism is a fringe academic theory discussed in coffee houses, with no mass union movement to give it teeth. Monarchies remain secure, their armies small and their populations dispersed.